Trip Report

Friday evening we established a good base camp in the trees just above the old Sunshine Shelter area, about the only area that was snow free. The snow revel at Sunshine was still above the Pacific Crest Trail sign, but we were able to dig the snow away at one spot and locate the stream for our water.

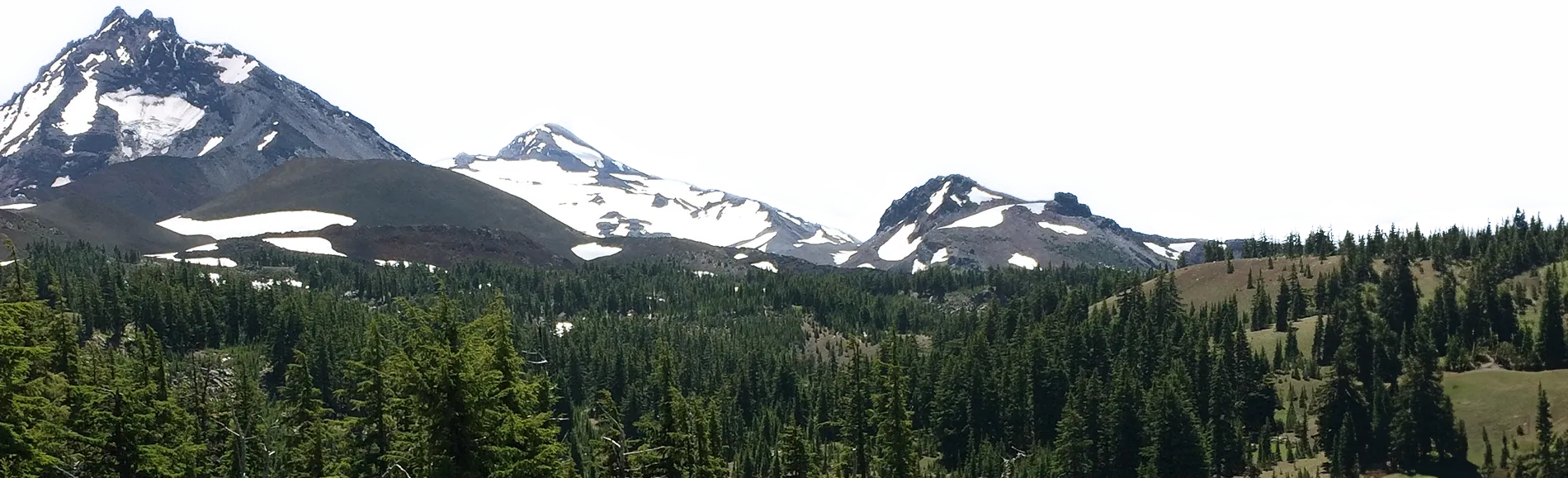

Saturday morning was clear and for a few minutes looked promising, but very quickly a cloud cap formed over the Middle Sister and by the time we had reached Collier Glacier, the North Sister summit and south ridgeline was rapidly being engulfed with blowing cloud plumes gusting from east to west. As the weather was now making the climb look marginal, the group decision was to proceed at least to the ridge. Crampons were put on in the dry and sheltered area of the rocks before proceeding onto the glacier and the ridge ascent was made straight away in good fashion. Upon attaining the ridge, I was surprised that the wind was not as strong as I had anticipated and the front from the west was still some ways off; so, feeling better about the situation, we proceeded toward the summit. The shadows of the blowing cloud plumes from the ridge onto the glacier below was awesome, like huge fingers of pulsating fire - How small we are!

The first steep pitch encountered on the ridge was negotiated along the snow and rock interface as the rock provided good hand and footholds. From the top of this, chopping steps commenced and became routine including the second pitch, where the natural route is forced around to the east side of the mountain. This is the accident chute on the return at about the 9800 foot level. At the top of this, I had the group divide into tope teams as the short snow traverse across to the saddle below the false summit was too steep without belays. Using the same teams, we proceeded to start on the summit snowfield. The snow field was big, extending around from its west face to the south and almost to the saddle at least 2½ to 3 rope leads across. To save time chopping steps, we dropped slightly down from the saddle on rock, then up on snow to the south ridge of the field. I set the first picket about 1/3 the way up the slope and the second picket just around the ridge on the west face; the objective being to have two pickets on a rope team at any one time. Mark Perrin was my rope team and belayed my progress. I had proceeded to about midpoint of the field and had set the third picket when we essentially ran out of time, weather, and for me, much of my stamina. The front was closing in and we were still, by my estimate, at least an hour away from the summit. Chopping steps is a snail's pace at best, making it agonizingly slow for those waiting and with the first spits of snow and the time of day, about 1:30 p.m., we decided to stop the climb. (In retrospect, an earlier departure time of about two hours would probably have given us the time we needed to make the summit. I should have allowed for more time lost in chopping steps especially this year with the snow staying so long, but the ridge route from camp had looked clear, so did not consider this additional time element.)

I passed the word back to proceed back to the saddle and on down through the rope-up chute before unroping. When Mark and I arrived at the top of the chute, one party was down and past the chute, the second party was in the process of descent and the third was waiting. I wanted to go ahead and asked Mark if he wanted a rope belay. He said "No" and we coiled our rope; he carried the pickets and I took the rope, carrying it across the right shoulder and under the left arm, and stepped across the top of the chute to the right of and outside the fall line of the descending group. I'm not sure, but in crossing over and as I remember, in a few big strides, at least my right crampon became balled with snow and on turning down slope I remember stepping with the left then looking down and saw the balled crampon of the right and mentally saying that's not right, but the mechanics of the stride put the foot down and I was airborne, feet first and backwards to the slope. (Obviously, I did not consider the slope too hazardous or I would have remained roped. I still don't consider it as overly hazardous. I had, of course, instructed the others to remain roped. My problem was in not being more cautious and prepared in starting my descent and having too much confidence in my crampons. My nemesis was the speed I attained before getting around into some sort of self-arrest.) I do not remember twisting into a self-arrest, but do recall vividly being in a classic No-No position of being only part way around facing the slope. The point of the ice axe was opposite my face, with the point at an angle into the snow. My hands were correct on the axe, but I was not able to get sufficient weight against the point and I was continuing to accelerate. Unfortunately, there is no second chance. Mentally, I remember my thought being that this shouldn't be happening and as I increased in speed I knew I was going into the rocks. The axe point hit hard ice near the bottom and twisted out putting me into a free fall. I went into the rocks feet first, basically on my stomach and at a fairly good speed. My left foot must have hit rock first, twisting and rolling my body to the left so that it was almost horizontal to the slope with my back down slope. Probably at this same time the left crampon collided with my right leg, just below the knee. I remember being horizontal and having my helmet and backside slamming the rocks and finally sliding to a stop, again feet first down slope but facing outward. My glasses were still on. The rope and pack were lodged in the rocks and prevented me from sliding further down the slope. The length of the fall I would estimate at 75 to 100 feet. There is no doubt in my mind that my day pack, the coiled rope around me and my hard hat, saved me from a more serious injury if not my life. Other than my left foot, the full impact had been taken by my backside and head. I was not stunned nor in any pain, I just laid there listening to the others working their way to me. My breathing was shallow and I felt slightly nauseous - the onset of shock. After checking me over for broken bones and stopping the bleeding in my leg, I was made as comfortable as possible and kept warm with additional clothing. I was still in shock and had difficulty in focusing my eyes across to the Middle Sister and my arms were tingling. All systems of blood going away from the brain. (In retrospect, the shock period, probably could have been lessened by moving me into a horizontal position, but the steepness of the slope made this difficult to do.) It took about a ½ hour before I felt well enough to stand and to see what kind of shape I was in. It didn't take but a step or two to realize that my left ankle was really hurting and progress down would be very, very slow and with this knowledge, we sent Sally Grosscup and Mark ahead and out to notify the Sheriff. (I had the climbing accident report form in my pack, but did not remember it was there to be used for just such an occasion as this.) Our primary objective was to be on the top of Collier Glacier, and secondly, if possible, back to base camp. I mentally made the decision that we must get off the mountain and to base camp, if at all possible, as I could not accept the thought of spending the night on the glacier with the difficulties this would present to myself and others. We had at this time about 7 hours of daylight remaining.

We used several innovative procedures, I think, in getting me off the mountain and back to base camp. I used two ice axes as crutches and besides helping to relieve the weight on the left ankle provided stability left and right but left me very unstable fore and aft. To counter this, we secured a short line between my waist sling and John Jacobsen's, who kept me upright by staying right behind me. He in turn was belayed with a rope by Tom Donnelly. This was slow but sure and worked very well and we proceeded slowly down the ridge; about half way off the ridge, descending down to the glacier, we tied two ropes together and made a fixed line down the slope and used shoulder belays. This also proved quite successful in speed and ease of descent.

Going up and over the glacier, across the rock field beyond and to the start of the steeper descent to base camp, I alternated between the ice axe crutches and being carried between John and Tom, similar to moving an injured football player off the field. The weather at this point was in a state of flux, in and out, but definitely deteriorating. Because of this, the group stayed together, as visibility was variable and with the complete cover of snow, the correct direction down was not the best. At this point, we fashioned a sled using Tom's parka and my ensolite pad as the sled and tied two slings together for the pull on the front and one of the ropes in back for a belay. I laid on my back with my legs either in the air or slightly touching as kind of out riggers. John pulled and guided, Tom acted as the belay. This worked extremely well and we lost elevation as fast as any group would descending normally and brought us to within about a mile of base camp where the flattened grade, sun cups and snow troughs made it too difficult to pull and we resorted back to being carried and using the ice axes as before.

At this time, we met two climbers from a nearby Mazama Middle Sister climbing party, who had been informed of our plight by Sally and Mark and were coming to our aid with overnight gear and provisions. One of these gentlemen, Doug Hall, had EMT training and came with us to our camp, checked me over and saw that I was warm, dry and bedded down for the night.

We arrived at camp a little after 8:00 p.m., about 6 hours from starting after the accident and within an hour it was dark and becoming stormy. (In retrospect, at this time, we should have sent word on out as to our location and condition. This would have helped and eased greatly the rescue effort. This was not done and I have apologized to the rescue people for this oversight.) I spent a reasonably comfortable night although, I believe I still owe John a box of aspirin.

Early the next morning, under clearing skies, the throb of a helicopter could be heard coming up from below. Naturally, they did not know our position and overflew to the mountain for their search. Everyone was out waving their brightest clothing, pads, etc., including the Mazama party, who had aborted their climb earlier because of the storm. Finally, after what seemed an eternity, they saw the groups, swooped in, landed, and had me in their stretcher and airborne in a matter of minutes. Also, in less than 15 minutes, I was up and over the mountain, landed and in the emergency room of St. Charles Hospital in Bend. Extremely efficient. (Except for trying to find one of my veins for an I. V.) The extent of my injuries were torn ligaments to my left ankle, cuts and abrasions to my right leg below the knee, and multiple bruises on my right backside and leg.

I have, by previous correspondence, thanked the rescue groups and the Mazamas for their efforts in helping me, but I want to thank them again, and each individual involved, more publicly through this report. The rescue units were the Lane County Sheriff's Search and Rescue and Mounted Posse, the Explorers Post 178, the Eugene Mountain Rescue and the USAF Pararescue Unit from Portland. As a citizen, and a climber, I am proud of them and very glad they are there when needed.

We are all experts at hindsight and all kinds of "if" scenarios can be made, but what happened, happened and I hope that in detailing this climb, others may benefit. I have, certainly. I'm very lucky, not only to be alive, but to have had so many wonderful and beautiful people touch my life; and that's what it's all about.

The wonderful people who made this climb and shared this experience with me were Tom Donnelly, Sally Grosscup, Jan Baker Jacobsen, John Jacobsen, Mike Nichol, Mark Perrin, Chris Shuraleff, Shirlynn Spacapen, and Gerry Tomseth.

- Leader, Glenn Meares

North Sister Rescue - The other view

Saturday 7/18/83 7:30 p.m. Sgt. Ned Heasty of the Lane County Sheriff's Office notified me as initial contact for Eugene Mountain Rescue, that Mark Perrin and Sally Grosscup had reported from McKenzie Bridge that Glenn Meares was injured on the North Sister. Ned requested an EMR callout be immediately initiated. He had already contacted the State Emergency Services Division in Salem; this would be known as State Search & Rescue Mission No. 20 83-034.

Sketchy details necessitated planning for a "worst case" scenario of the entire climbing party, without overnight gear, still at the accident site near the summit snowfield. The stormy weather and Glenn's unknown condition added to the concern. For a litter evacuation from high on the mountain, 15 fully-equipped climbers were sought, along with considerable backup support.

During the next two hours, Ned called members of Lane Co. Sheriff's Mounted Posse, and Explorer Search and Rescue Post 178, while I contacted EMR climbers. As Search Coordinator, Ned also checked on helicopter availability with the Oregon Air National Guard, the USAF 304th Rescue Squadron and Life Flight in Portland, and private air ambulance in Eugene.

11:00 p.m. Only 7 climbers were now available, but the 304th had been lined up after reams of red tape, including contact with Scott Air Force Base in Illinois. Weather forecasts were steadily improving, however, and flying became a real possibility. Full ground personnel would still be needed in case flying weather again deteriorated.

1:30 a.m. Sunday. Three more climbers had been reached, and final plans completed. Went to bed for a very short 2 hours.

4:00 a.m. EMR and 178 grouped at the Lane County Shops to begin a wild and stomach-upsetting ride up McKenzie Pass in surplus Army vehicles (including one on which the back door kept flying open).

6:00 a.m. All ground teams were assembled at Frog Camp: 1O EMR climbers including Obsidians John and Peter Cecil, and Bert Ewing; 4 members of the Mounted Posse with 7 horses; 6 Explorers and 3 adult advisors from Post 178; and Search Coordinator Heasty. Except for Ned, all 24 were unpaid volunteers.

8:00 a.m. Two helicopters of the 304th, each with a two-man pararescue team arrived from Portland. They would make the initial attempt to find and rescue Glenn. If they failed, the Posse could transport climbers and equipment to the White Branch lava flow. Beyond that point, snow prevented the use of horses. EMR would then hike in with climbing gear and a break-apart akja (ski-sled). Explorer Scouts would maintain a base at Frog Camp and provide lower-elevation support. Glenn would be transported by akja to White Branch, then if his injuries allowed it, by horse to Frog Camp. If he could not ride horseback, the Explorers would transport him down the trail in a wheeled stokes litter. An ambulance, if needed, would then carry him to a hospital.

None of the above ground-transport methods are particularly comfortable for an injured person, but fortunately the 304th was able to locate and pick up Glenn from the Sunshine Meadows area and fly him directly to St. Charles Hospital in Bend (I hear he put up a valiant fight when the medics tried to shove an I.V. in his arm).

All search personnel returned to Eugene by noon Sunday, except for Stu Rich who took advantage of the break in the weather to attempt a climb of Middle Sister, and Posse members who took a quick ride up the trail.

Participants in the rescue:

Search Coordinator - Ned Heasty, Emergency Services Division, Lane County Sheriff's Office (and considerable County resources.)

304th Aerospace Rescue and Recovery Squadron, Portland - Operations Officer Maj. Fred Stovel; 2 Huey helicopters each with 2 pilots, 1 crew chief, and 1 2-man pararescue team.

Eugene Mountain Rescue - Bud Proctor, John Cecil, Peter Cecil, Stu Rich, Tom Johnson, Jim Blanchard, Dave Reuter, Keith Nelson, Ron Lyman, and Bert Ewing.

Mounted Posse - Jack Flint, Mike Ramberg, Ted Hansey, Jay Keenon, and 7 horses.

Explorer Post 178 - Jack Pendell, Erick Antonson, Adam Strasdas, Debra Hubbard, Alison Mann, John Riggs, and advisors John Pitetti, Jane Strasdas, and Brian Wedmore.

Critique:

No gross negligence or significant poor judgment seems to have caused this accident. Rather, it was the result of several minor (and usually only annoying) causes which are common to mountaineering: snow balling up under a crampon, wearing crampons longer than necessary, and fatigue. Lack of a belay and failure to self-arrest in poor snow compounded the situation. The combination just went against Glenn this time. On the plus side, Glenn's pack, coiled rope and hard hat probably prevented serious injury. (Only three years ago a rope team slid off the nearby summit snowfield and into the rocks below. One person was killed - he was not wearing a hard hat and suffered massive head injuries).

On only one point could the Obsidian party have done better, and given the circumstances when they reached Sunshine, criticism can't really be justified. News from the mountain was non-existent after Mark and Sally came out with the initial word of the accident. If someone else could have hiked out with more information as soon as Glenn's party reached Sunshine around 8:30 p.m. Saturday, the rescue planning could have been more direct, and perhaps not as major. There's a world of difference between anticipating someone critically injured at 9000 feet on North Sister in a driving storm without overnight gear, and knowing that that same victim is warm and snug in a sleeping bag at Sunshine Meadows, in relatively good condition. On the other hand, of the two climbers who initially hiked out, only one was questioned about the accident. Though probably nothing different would have occurred, important information could have been omitted or misinterpreted.

For anyone involved in future mountain accidents or searches, it should be remembered that lack of information is often the greatest problem for the rescuers. Write down (don't attempt to remember in your head) the names and conditions of all members of the party, detailed descriptions of any injuries, relatives or friends to contact, the exact location of the victims, and the plan of the party at the accident site. Finally, be prepared to spend a night; it's very rare for a mountain rescue in Oregon to occur until at least the following day. The Sheriff of the affected county should be contacted immediately; he is the one legally responsible for all Search and Rescue in Oregon; no volunteer rescue groups can legally be activated except at his request. (If this accident had occurred 300 feet away, on the East side of the ridge, Deschutes County would have been the co-ordinating agency - an interesting point to ponder the next time you're straddling a county line on one of our mountain ridges).

This rescue also points out the massive resources which are available and triggered by an emergency. Rescue is taken seriously by Lane County. There is no "partial" rescue if someone is lost or injured enough that official help is requested. Certainly the fact that Glenn ended up in a leg cast justifies the major concern to get him off the mountain.

On this rescue (and others) most of the rescuers are volunteers - they contributed 264 person-hours - and it must be remembered that no one forces them to do this. For Ned, it's all in the job (he's always cheerful at two in the morning!). The major expense was the flight time of the 304th - but if they weren't on actual missions, they'd be flying training missions to keep current; the crews would rather fly "real" missions anytime. A sobering point, however, is that if private air ambulance had been available, Glenn would have been billed for their service at $800/hour. Actual cost to Lane County on this rescue was an estimated $417.00.

All in all, no major mistakes seem to have been made. The Obsidian party made excellent decisions and use of their available resources to get Glenn safely and quickly off the mountain.

- Bert Ewing

.